New rules requiring donated livers to be offered for transplant hundreds of miles away have benefited patients in New York, California, and more than a dozen other states at the expense of patients in mostly poorer states with higher death rates from liver disease, a data analysis by The Markup and The Washington Post has found.

The shift was implemented in 2020 to prioritize the sickest patients on waitlists no matter where they live. While it has succeeded in that goal, it also has borne out the fears of critics who warned the change would reduce the number of surgeries and increase deaths in areas that already lagged behind the nation overall in health care access.

Show Your WorkOrgan Failure

How We Investigated UNOS’s Liver Allocation Policy

We found that new requirements led to plummeting transplants in some poorer states while New York and California saw big gains

The analysis of data from federal health authorities found sharp declines in life-saving surgeries in Puerto Rico and seven states, all but one Southern or Midwestern: Alabama, Louisiana, Kansas, North Carolina, South Dakota, Iowa, and Pennsylvania. Meanwhile, New York and California, whose transplant industry officials lobbied for the new policy, logged their highest numbers of liver transplants in more than a decade in 2021—603 and 959, respectively.

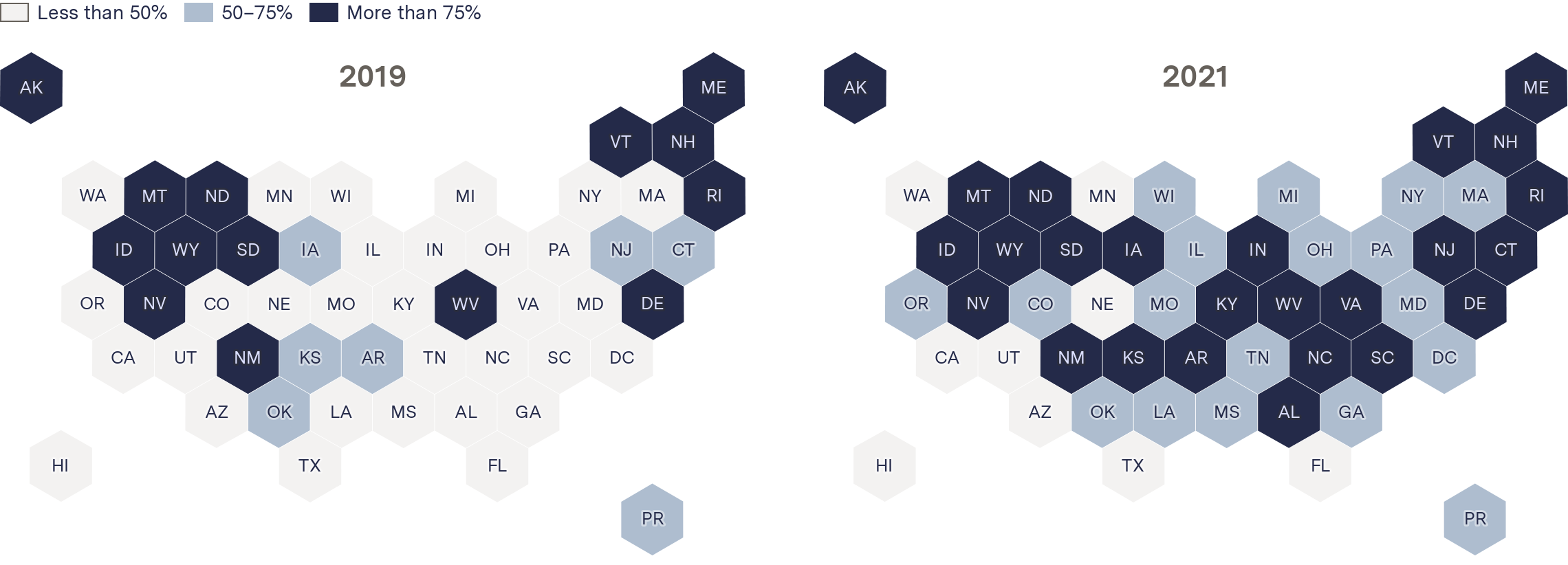

The new system, called the “acuity circles” policy, has nearly doubled the median distance livers are transported, increased transport costs, and coincided with the highest number of wasted livers in nearly a decade, 949 in 2021. That’s one in 10 donated livers. The analysis further shows a significant increase in the number of states sending donated livers beyond their own borders. In 2019, before the new policy took effect, 21 states and territories exported a majority of livers they collected. Two years later, 42 did.

“You’re reforming an organ allocation policy so that it rewards the wealthy areas and wealthy states by providing resources from poor areas of the country,” said Seth Karp, director of the Vanderbilt Transplant Center in Nashville. “I just find that really troubling.”

Karp’s criticism comes amid increased congressional scrutiny of the contractor that has overseen the nation’s organ donation system for the federal government for nearly four decades, the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS). The House and Senate are probing whether it and several of the 56 “organ procurement organizations” that it oversees are effectively carrying out their duties, including collecting enough organs for transplant, among other issues.

In an August hearing, Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) called the system under UNOS a “dangerous mess.”

In written statements to The Markup and the Post, UNOS acknowledged that donated livers are now being transported twice as far on average but defended the changes as better allocating scarce resources to serve the sickest people on the transplant list, in compliance with federal regulations.

Organ Failure

How a Group of Health Executives Transformed the Liver Transplant System

Hospitals in New York and California engineered a policy shift that let them source livers from hundreds of miles away

“I’m proud that UNOS distribution policies are today saving the lives of the sickest Americans no matter where they live, and we are now leading more improvement to further increase efficiency, accuracy and transparency across the system,” UNOS interim CEO Maureen McBride said in a written statement. No one at the organization would agree to speak to reporters about the policy despite repeated requests.

The data shows that the gains UNOS referenced came at a high cost for patients in a handful of states. In Alabama, for example, where twice as many people die of liver disease per capita than in New York, adult liver transplants fell 44 percent under the new rules, to 72.

These reductions occurred even as the number of transplants and donations nationwide continued to trend upward, largely because increased opioid overdose deaths have made more organs available. In Louisiana, adult liver transplants dropped 27 percent in 2021 despite a high donation rate of four livers per 100,000 people—more than double that of New York.

Some states that did not appear to be part of the lobbying process also increased transplant volume under the policy, notably Oklahoma and Utah.

The change made very little difference for about a third of states when comparing their overall transplant numbers from 2019 to 2021. But a secondary analysis looking at transplants as a percentage of the organs donated in each state resulted in more polarized findings, with a total of 19 states and Puerto Rico showing a reduction in transplants and 12 states and Washington, D.C., an increase, leaving just six states essentially unchanged.

In its own reports on the effects of the change, UNOS found that patients’ survival rate within a year of their transplant dropped from 94 percent to 92.8 percent in the first 18 months, leveling out by early 2022 to about 93 percent. In written statements, spokesperson James Alcorn said an increase in deaths among the newly transplanted is to be expected when those patients are sicker. He pointed out that fewer people are dying on the waitlist overall nationally.

Liver distribution decisions are contentious because every year, more than 1,700 adults on average die or get so sick they are no longer a viable candidate for a transplant.

“It’s all extremely upsetting to think that you are not good enough,” said Mae Ruddock, 58, of Aurora, Mo. The policy makes her feel like “the people on the coasts are the good people. And they’re the ones that deserve the best, and they deserve to live.” Her husband, Billy Ruddock Jr., 59, has waited more than a year for a liver transplant. Without one, his illness—nonalcoholic fatty liver disease—will kill him.

His nearest transplant center is 188 miles away in Kansas, where transplants have dropped by a third since the policy change, according to the analysis. UNOS said the number of waitlisted patients who have died in that state has increased by more than 10 percent since the policy change.

Alcorn said the policy is meant to be neutral. “The OPTN’s only interest in developing the liver policy was to save the most lives through liver transplantation while complying with” federal regulations, he said, referring to the system that UNOS operates: the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network. “To that end, the policy deliberately does not ‘reward’ any area of the country or ‘punish’ any area.”

Giving Up

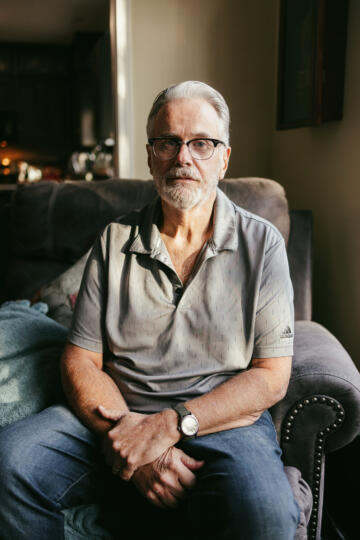

Another Kansas patient, Gary Gray, waited for a donated liver for so many years that he and his wife finally gave up on the system.

Gray, 64, of Olathe, Kan., has an autoimmune disorder that began shutting down his liver in 2019, leaving him with a host of health problems including fatigue, tremors, and shortness of breath. His dying liver gave him such severe brain fog that he had to retire two years ago from his job in IT infrastructure. Under the old policy, his surgeon said, he would have gotten a donated liver long ago.

The University of Kansas Health System is the only hospital in the state that performs liver transplants. In 2021, the first full year after the policy change took effect, it performed 30 fewer surgeries than in 2019—down more than a third. Timothy Schmitt, head of the transplant unit there, said his patients are waiting much longer and need to become much sicker now to receive a transplant.

He called the new policy “the most backward plan that was ever created.”

After more than three years on the transplant list, Gray had gotten so weak he had to take a break while walking the eight feet from his recliner to the kitchen. So he and his wife found a living donor through Facebook, bypassing the traditional transplant system altogether.

Living donor transplants are rare in the United States, which relies overwhelmingly on organs collected after death. The procedure removes only a portion of the donor liver and transfers it to the sick patient. Both pieces regenerate to full size.

Alcorn said Gray’s situation is not a result of the policy change because his donor was living. He did not address Gray’s complaint that he felt he had to seek a living donor because the system was failing him.

A Legal Challenge

The UNOS policy change came after aggressive promotion and intervention by hospital and transplant officials in New York, California, and Massachusetts, who complained for years that very sick patients in their states were forced to languish on long waiting lists while less sick patients elsewhere got transplants more quickly. According to interviews, hospital officials recruited patients in those states and funded a 2018 lawsuit filed on their behalf demanding that livers be shared more broadly.

The most backward plan that was ever created.

Timothy Schmitt, University of Kansas Health system

At the time, UNOS and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), which oversees the nation’s organ donation system, said the lawsuit prompted them to approve the new rules in a matter of months, overruling a committee of liver experts who recommended a plan that would not result in livers traveling as far. They also rejected another reform plan that had been approved by the UNOS board—but not yet implemented—that came after five years of study and consideration. While in many cases federal agencies establish rules, in this case, UNOS makes rules with input from the greater transplant community, and HHS approves them.

To examine the impact of the new policy, The Markup and the Post analyzed five years of data obtained from federal health regulators through public records requests on donated livers, liver recipients, and organ discards, as well as data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The analyses tracked where each organ originated, how far it was transported, and where it was ultimately transplanted. Thirteen states do not have a liver transplant program but have residents who donate organs; they were included only in the distance analyses.

Organs are transported nearly twice as far under the new policy—a median of 163 miles in 2021, up from 85 miles in 2019—the analysis shows.

More places exported a majority of their donated livers in 2021

Percent of livers exported

2019

2021

UNOS acknowledged that organs are traveling twice as far. But it said its own internal analysis shows that livers have spent, on average, only 10 minutes more outside the body as a result of the policy change. UNOS declined to share the underlying data for that analysis. All of UNOS’s reports and responses to reporters’ questions use data that includes child transplants, which The Markup and the Post did not include because their health issues and the algorithm determining who gets the donated organ are somewhat different from adults’. Adults make up about 94 percent of transplants.

HHS declined to respond to written questions. Its subdivision the Health Resources and Services Administration, which contracts directly with UNOS, also declined to answer questions but issued a brief statement.

“The Biden-Harris Administration prioritizes transparency, accountability and equity in organ procurement and transplantation and will continue to assess the current liver acuity circle allocation policy,” wrote spokesperson Elana Ross. Ross noted that more than a dozen hospitals in the Midwest, South, and Oregon have sued to overturn the policy, arguing in a 2019 lawsuit that UNOS lacked legal authority to radically overhaul the organ distribution system set up by Congress in 1984.

In written responses, Alcorn pointed out that some of those that are suing benefited under the change and that they make up a small subset of about 140 liver transplant programs in the nation. He said the hospitals are fighting to avoid losing as much as $200 million a year in revenue from a reduction in transplants. The lawsuit is ongoing.

He also noted that the February 2020 implementation of the policy change coincided with the beginning of the coronavirus pandemic, the effects of which are still being studied as they relate to transplants. The data shows a precipitous decline in transplants across the board in March 2020, with an uptick a few months later back to pre-pandemic levels. The Markup and the Post did not include data from 2020 to reduce the effects of the pandemic on the overall analysis, and instead compared data from 2019 to data from 2021.

The Algorithm

Arguments over livers are heated because there aren’t enough to go around. Last year, although more than 9,500 liver transplants were performed, about 10,000 sick people remained on the waiting list across the country at the end of the year. Livers are the second most transplanted organ after kidneys.

End-stage liver patients have a uniquely urgent need: a transplant is the only option for survival. There is no stopgap treatment, such as dialysis for kidney disease.

UNOS operates a different algorithm for matching each of the various transplantable organ types to waiting patients. When a liver becomes available, UNOS’s liver algorithm considers dozens of factors to find a recipient who is physically compatible (blood type, patient height) and has the greatest need (severity of illness, time on waiting list).

Under the old rules, one of the most important factors was location. The algorithm’s search started in the “donation service area” immediately around the hospital where the donor died. These varied greatly in size and population. According to federal organ procurement data, the smallest donation service area was about 3,600 square miles, while the largest was about 808,000 square miles; populations ranged from 1.4 million to 20 million. If no match could be found in the service area, only then would the system offer the organ to patients in the broader region, which typically encompassed several states.

The new policy instead searches for the sickest compatible waitlisted patient within a 575-mile radius, which is equivalent to more than one million square miles, around the donor’s hospital. In New York, for example, this would give patients access to livers as far away as Ohio. If there are no takers among those in the larger circle, UNOS offers the liver to patients who are less sick within 173 miles of the donor, then 288 miles, then 575 miles. It repeats this process, offering to patients who are less sick each time, eventually opening it up nationally.

Landing a spot on the transplant waiting list has been difficult for some time. The proportion of people who make it can vary wildly by state. In 2021, Massachusetts had 11 people per 100,000 residents on its livers waitlist—the second-highest in the country; North Carolina had one per 100,000, among the lowest nationwide. Kansas had about three per 100,000.

To get on the list, patients need insurance or other means to pay for their treatment. They must show up for regular appointments, which often require access to a car and sometimes a friend or family member to drive. And they have to be able to pay for regular appointments before transplant surgery, weeks of recovery at the hospital afterward, and thousands of dollars a month in anti-rejection medication for the rest of their lives.

Residents of the states harmed by the new rules are at a disadvantage for each of these. Not only do they generally have lower incomes, they also have lower rates of insured people than those that benefited. Three of these seven states chose not to expand Medicaid, the federal health program for the poor, under the 2010 Affordable Care Act. A fourth, South Dakota, only expanded it in late 2022, and it doesn’t go into effect until this summer. The state has the second-highest rate of death from liver disease in the nation.

Lack of insurance leaves many people with no way to pay for a liver transplant, which can cost just shy of a million dollars.

“Everyone has to have insurance,” said J. Steve Bynon Jr., chief of abdominal transplantation at Memorial Hermann in Houston, when asked about its policy. “There are no freebies.”

Then there’s the cost of just getting to the hospital door. For residents of many states, including those now performing fewer transplants, the nearest surgical center is often hours away. The states that suffered under the policy have fewer liver transplant hospitals per square mile than those that benefited.

Making the List

John Lewis, 38, a liver patient in rural Alabama, must drive 180 miles to Birmingham—about three hours each way—at least once a month to undergo screenings to get on the state’s transplant list.

Because of an accident a decade ago, Lewis’s only income is from the Social Security disability insurance program. His partner, Ava Williamson, cares full time for her mother and Lewis. A recent hospital visit “would’ve been impossible,” Lewis said, if a friend hadn’t given him $300.

Another common requirement for getting on the transplant list is controlling any existing infections—including minor dental infections, which often are not covered by traditional medical insurance. Lewis said he had to drive an hour to a dentist willing to pull two of his teeth and give him two fillings.

“Being poor,” said Donna Cryer, CEO of the patient advocacy group Global Liver Institute, “penalizes people.”

Even when patients make it onto the waitlist, some factors that affect the poor are not counted. The numerical score from six to 40 used to measure the severity of a patient’s liver disease, called a MELD score, does not take into account other medical conditions a patient may have, such as hypertension or diabetes, which are more prevalent in rural states.

People with those conditions, in comparison to others with the same MELD score, are more likely to die while awaiting a transplant, said Schmitt, of Kansas’s transplant unit. That’s not only due to illness but also because they are more likely to become too frail to receive a transplant at all.

Being poor penalizes people.

Donna Cryer, CEO, Global Liver institute

“There’s this assumption that if your MELD score is 29 and you live in rural Appalachia, you’re just as sick as someone who lives in downtown Manhattan,” said Jayme Locke, director of transplantation at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. “They may have the same medical score, but they come with far more comorbidities and are much sicker” and they die much more often, she said.

In 2017, UNOS’s CEO at the time, Brian Shepard, privately dismissed such concerns as “an infuriatingly elitist argument masquerading as concern for the poor” in one of hundreds of emails regarding the policy released as part of the lawsuit by Southern and Midwestern states.

“Only people who have means can get a transplant. So this isn’t a ‘give [transplants] to poor people’ argument,” Shepard wrote to the head of the organ procurement organization in Massachusetts. “It’s a ‘give [transplants] to those of us who have to live near poor people’ argument.”

Shepard, who stepped down as UNOS’s CEO in September 2022, did not respond to requests for comment.

Babak Movahedi, chief of transplants at UMass Memorial Medical Center in Massachusetts, said he sees both sides of the argument. He said access to care unquestionably leads to unfairness in who gets saved.

“I just don’t see how changing the allocation system would fix that, though,” he said. “I think that’s a much bigger problem and much broader discussion, which is really access to care in general.”

Increasing Costs

The increased distances also have created other problems because livers must often be flown. If the algorithm awards a liver to a faraway patient, finding a plane to get it there in time can be difficult, especially in areas without major airports. Kelly Ranum, CEO of the Louisiana Organ Procurement Agency, said her staff often have to drive to pick up livers, increasing the risk of deterioration.

Some organ procurement agencies avoid this by owning their own planes. New England Donor Services, which is based in Massachusetts, paid $5 million for a plane a year before the policy change, according to its federal tax filing and an interview with the firm that helped broker the purchase. Indiana Donor Network registered two planes in early 2019, months after the policy was approved.

But extra travel also drives up the cost of a transplant. Fuel, crew, and ground time for charter flights can be up to $50,000 for a single organ, according to several surgeons, organ procurement executives, and other experts. These costs are charged to transplant hospitals, which roll them into bills submitted to insurance companies, Medicare, Medicaid, or wealthy, uninsured patients.

Federal cost reports filed by 41 organ procurement organizations, accounting for 94 percent of all liver transplants in 2020 and 79 percent in 2019, show that travel costs increased for about half of the organizations since the rule change. New England Donor Services reported a $1.4 million increase in travel costs it billed to hospitals, up 160 percent. CEO Alexandra Glazier attributed the increase to a 300 percent increase in flights for livers in 2020 from the year before.

The Pennsylvania-based Gift of Life Donor Program reported an extra $1.1 million in transportation costs in 2020, up 86 percent.

The extra travel also has contributed to the increase in discarded livers, some transplant professionals said. While surgeons sometimes discard livers because the organs are in worse condition than expected, they can also be lost because they have been outside the body for too long. Livers are fragile and can survive about 12 hours outside the human body; being transported farther under the new policy means livers can rack up additional time outside the body if the first recipient declines it and it needs to be sent to a new location.

115%

Increase in livers rejected for "failing to locate a recipient" from 2019 to 2021

Source: UNOS

While there was not enough detailed data for The Markup and the Post to analyze the policy change’s impact on discarded livers, records show that 23 livers were rejected for being “too old on ice” in 2021, an increase of 53 percent from 2019. “Failing to locate a recipient” was cited as the reason for rejecting 84 livers in 2021, an increase of 115 percent since 2019. But that doesn’t account for the full increase; about a third of the discards were categorized as “other” without elaboration.

Alcorn, of UNOS, said a “hand count” of discard data shows “very few cases” where travel is listed as a cause. He did not address whether more were discarded because they were outside the body too long.

The South and Midwest have had higher organ donation rates per capita than other areas of the country for years. The reasons for this are complex, but experts say it’s because these states have a higher percentage of types of deaths that leave organs in good condition for transplants.

In 2020, for example, the South and Midwest reported higher than average rates of deaths from strokes, stroke-like conditions, and drug overdoses among adults, according to the CDC. Strokes and drug intoxication also led the causes of death for those who donated livers in both 2020 and 2021, according to an analysis of donor data by The Markup and the Post.

“If you have a lot of those types of organs in your region, it’s typically because your region is disadvantaged in some ways that would make people die these ‘donation eligible’ deaths,” said Keren Ladin, associate professor at Tufts University’s department of community health.

By contrast, the nonprofit in charge of procuring donated organs in New York—LiveOnNY—has been repeatedly criticized for doing a poor job and nearly lost its federal certification five years ago. The federal government changed the performance standards for all organ procurement contractors in 2021 with a goal of increasing total donations for all organs by 5,600 a year.

Karp, the Nashville transplant surgeon, said too few donations is the root of the issue with the transplant system. But increasing the supply of livers, he said, was never the focus of authorities.

“They completely missed the major problem,” he said.

Reporter Annie Gilbertson contributed to this story.